A Polar Comparison of Concussion Legislation in the United States and Canada

By Brandon Seltenrich

When it comes to prevention or treatment programs pertaining to sports-related traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), youth concussion protocol is typically the primary concern, as young children and teenagers participating in sport are the most susceptible to permanent damage stemming from a TBI. The United States and Canada have both taken different routes in addressing the youth concussion protocol, evident through proposed and passed legislation in recent years. Contrasting the two countries' treatment and prevention policy will shed light on the steps still needed to be taken to move in the right direction and protect the health of millions of athletes.

Traumatic Brain Injuries are caused by bumps, blows, or jolts to the head that disrupt brain functioning. It makes sense, then, that the leading causes of TBIs are falls, being struck by or against objects, and motor vehicle crashes. However, head injuries in youth sport are still a frequent occurrence and contributor to TBIs– across all sports.

In 2013, the United States counted approximately 2.8 million TBI-related emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. The economic burden is estimated to be approximately $76.5-billion, in large part from programs and services funded through federal and state sources that support TBI patients.

With the number of reported concussion cases and the ever-growing economic burden on the federal and state government, the United States has done a considerably good job from a legislation and policy standpoint on trying to combat concussion through prevention initiatives and treatment programs.

To fund services to those at risk of being institutionalized with a medical condition, Medicaid Home-and-Community-Based Services (HCBS) waivers are active in 47 states, and the District of Columbia. As of 2018, in at least 22 of those 47 states, an HCBS waiver to extend benefits and services to certain patients with TBIs is in place. This means that in 22 of the 50 states across the country, at-risk concussion patients are entitled to medical services if they are institutionalized. On a nationwide scale, that's pretty remarkable.

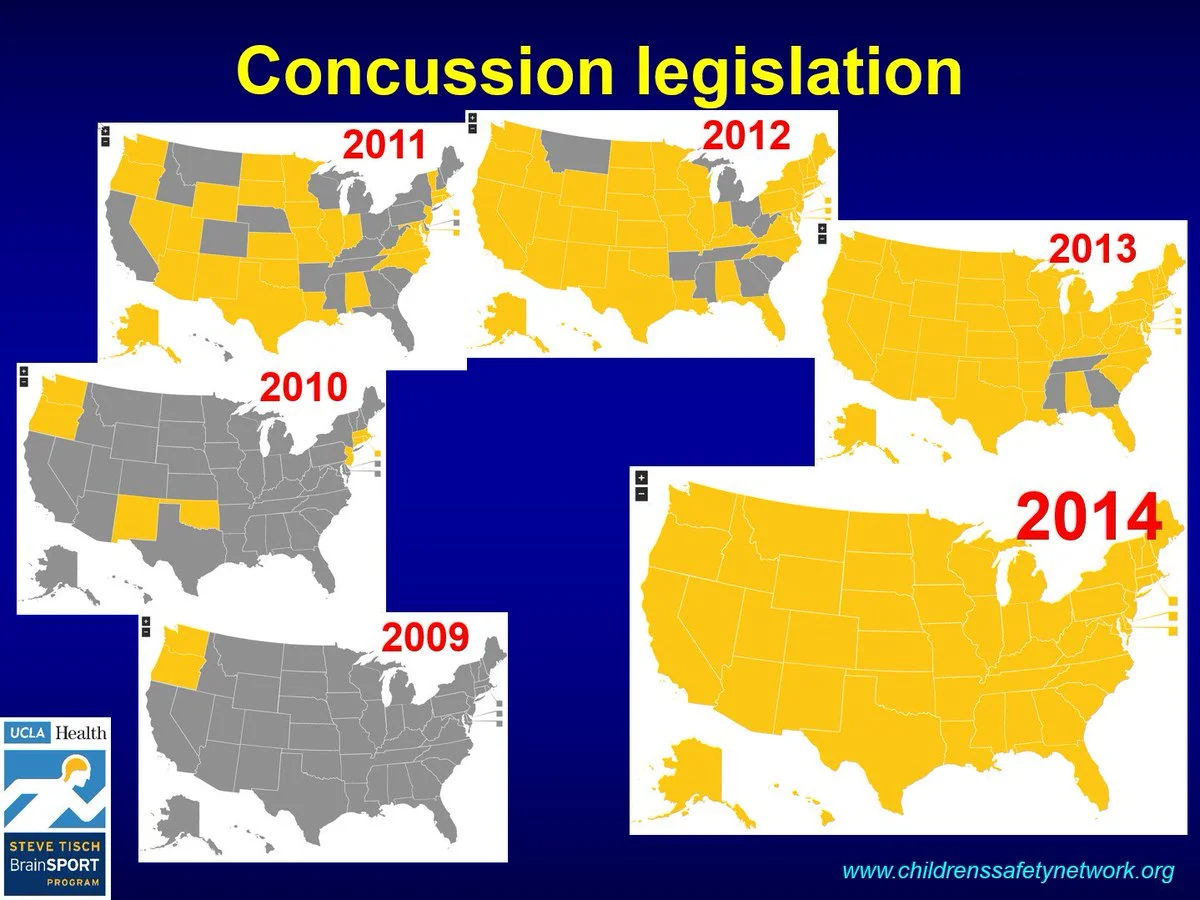

The implementation timeline of U.S. youth sport concussion laws

That goes for any patient who suffered a TBI from any source through any activity. Sports-related concussions, however, are their own, widespread problem. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey reported at least 2.5 million high school students across the U.S. were affected by sports-related concussions in 2017 alone. Many states have taken aim to prevent TBIs in youth sport, as well as find an effective method of diagnosing and rehabilitating patients.

While the number of athletes participating in youth sports affected by concussions remains high, the U.S. government has actually been working for a number of years to address the issue.

Between 2009 and 2015, all 50 states and the District of Columbia passed laws to address traumatic brain injuries, with the majority of those states enacting legislation specifically targeting youth sports-related concussions.

The introduced legislation appropriates funds to prevention or treatment programs of traumatic brain injury, and also requires insurers, hospitals, and health maintenance organizations to provide coverage for survivors of TBIs.

The vast majority of these laws share three primary components: first, education and training on recognition of and appropriate responses to concussion. Second, the protocol of removing youth athletes from play or practice if it's suspected they might have a concussion. Third, only letting youth athletes return to practice or competition after being evaluated and cleared by a designated health care provider.

All in all, concussion protocol, treatment and prevention policy in the United State has taken major strides and achieved significant accomplishments and milestones. In contrast, however, just north of the border, Canadian Parliament has failed to follow suit.

The foremost piece of Canadian legislation to be introduced to date is Rowan's Law, a piece of legislation whose namesake comes from the late Rowan Stringer, a high school rugby player from Ottawa, Ontario, who passed away 3 years ago after suffering Second Impact Syndrome due to sustaining multiple concussions suffered within a short period of time in consecutive rugby matches.

Rowan's Law is the first concussion legislation in Canada, named after the late Rowan Stringer

After Rowan's death, a coroner's inquest resulted in 49 separate recommendations to be implemented in an effort to prevent another tragedy like this one. A private members bill was put forth by Conservative MPP Lisa McLeod, along with Rowan's parents, Gordon and Kathleen Stringer.

On March 7, 2018, Rowan's Law passed unanimously at the Ontario Legislature, received Royal Assent, and became law in Ontario.

Rowan's Law includes implementing increased education and awareness for parents, coaches, athletes, and teachers surrounding concussion issues, providing better tools to coaches and trainers for identifying concussions, concussion policies in place at all school boards and sports associations across Ontario, and increased education and training among healthcare professionals, to better treat and manage concussions.

Right now, every state in the USA has some form of concussion-related legislation. With the passing of Rowan's Law, Ontario is the first and only province in Canada to implement such legislation.

Whether it be professional sport or youth sport, the fact of the matter is that millions of athletes suffer from and are affected by concussionsevery year, in both the United States andCanada. For two countries with a high percentage of sport participation, that much is expected. The path that is to be taken moving forward to address the issue of concussion, however, is what makes all the difference.

U.S. legislation, as it stands, is the model to follow for Canadian Parliament and all of the provinces outside Ontario, and fully adopting Rowan's Law is a good starting point to get the ball rolling.

With attention being drawn to the issue of concussion amid testimony before Canadian Parliament from powerful figures in sport such as National Hockey League Commissioner Gary Bettman, it seems that the time for progress is now, and the only way to go is forward.

Image sources: